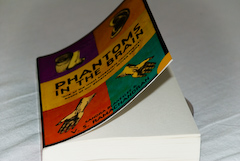

This is a non-fiction book on neuroscience. I nearly got scared too, but on the back cover was a recommendation from The Economist and so I decided to pick it up and give it a try. Turns out to be a wonderfully written, eminently layman-readable and a very interesting book.

The author examines a number of brain disorders in order to illustrate how the human brain operates and how complex and far-reaching the workings of this wonderful machine are. He starts off by examining the issue of “phantom limbs” – a condition whereby someone with a limb amputated can still vividly feel its presence. He moves on to discuss matters such as visual perception, evolution, consciousness and identity.

The best part about the book is that it discusses issues that are extremely complex, but very simply illustrated – the only prerequisite being (I felt) a sense of wonder. Dr. Ramachandran’s writing is anecdotal and often humourous, and illuminates the methods of brain science very well. One of the main themes of the book is that the brain is divided into a number of modules which can function independently of each other; thus leading to the concept of many “phantoms” or “zombies” in the brain, even though for most people their identity seamlessly coalesces into one entity. For example, he writes about experiments that decisively show that the part of the brain which judges the size of a coffee cup is different from the one that instructs your fingers to move apart to grasp the cup, and it is yet another part which allows you to actually perceive that the coffee cup is moving toward your lips. This seems quite mundane until you actually read about someone who can pick up the coffee cup effortlessly, but at the same time claims that she cannot really identify the object in question as a coffee cup. It’s amazing to read how many processes come together in order for us to experience life as we know it.

The book also links social behaviours and evolution to the brain. Of course, nobody will be surprised to know that mental ability and even hand-eye coordination may be a function of how your brain is wired up; but even social traits like being talkitive and egoistic are controlled to some extent by brain wiring.

Overall a lovely read for anyone – even if you’re not interested in the workings of the brain or in science generally, this book will probably generate some interest in you.

Rating: 4 / 5

Post a Comment